Quick Link:

學生/学生、今天、很冷、好人、你好嗎/你好吗、很多、姓王、小朋友、中文、地方、他的、你們/你们、我們/我们、美國/美国、都、真好、太好了、可是、有名、你叫什麼/你叫什么、知道、認識/认识、什麼/什么、一個朋友/一个朋友、你呢、好吧、喜歡/喜欢、和氣/和气、不對/不对

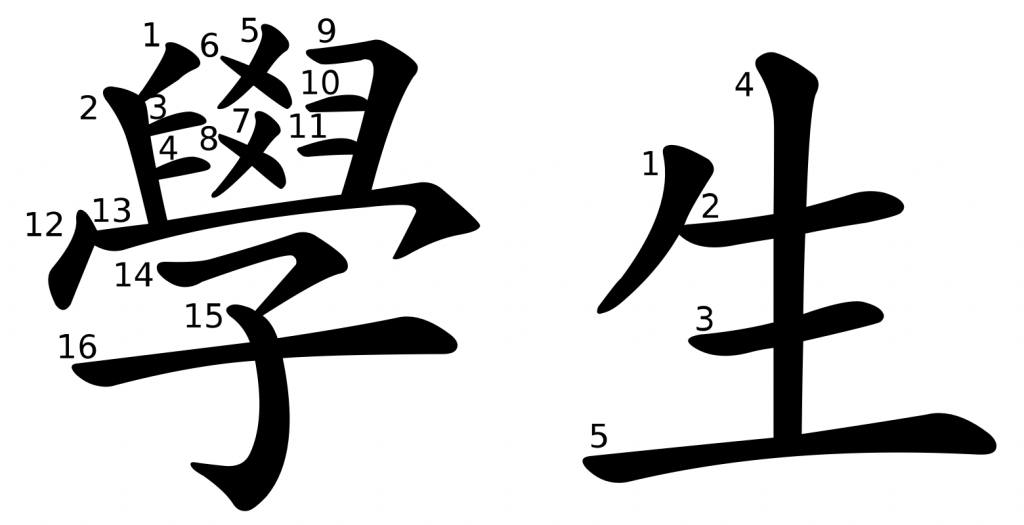

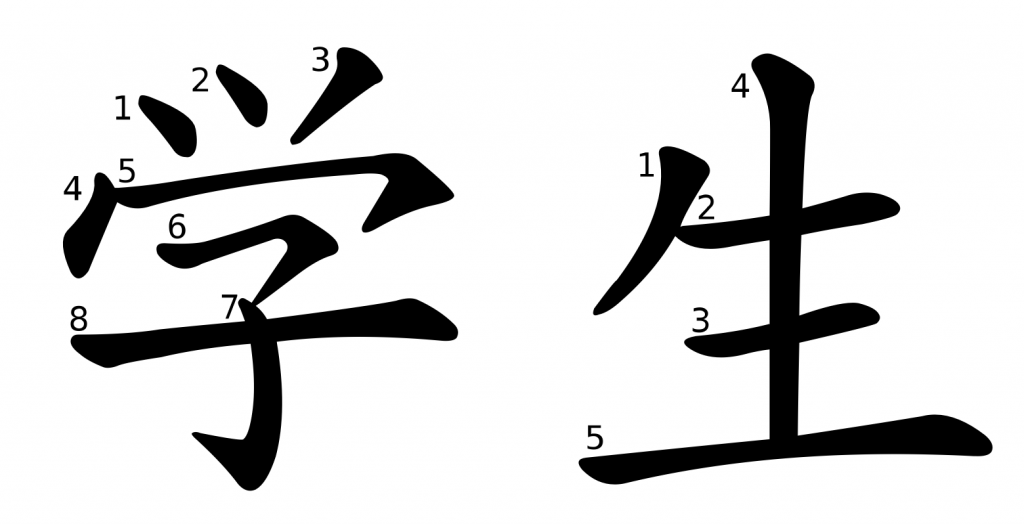

學生/学生 n. [xuésheng] student. 我是學生/我是学生。I am a student.

xué: to study, to learn

radical: 子 (zǐ; This radical is usually associated with Chinese characters that have meanings related to people)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The original meaning of the character “學” (xué) is “awakening.” In bronze script, the component “子” (zǐ) represents a child, while “冖” (mì) signifies a state of ignorance. “臼” (jiù) is a phonetic component, representing the sound of the character in ancient times. Because a child is ignorant, they need to learn.

shēng: to grow

radical: 生 (shēng; to give birth)

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

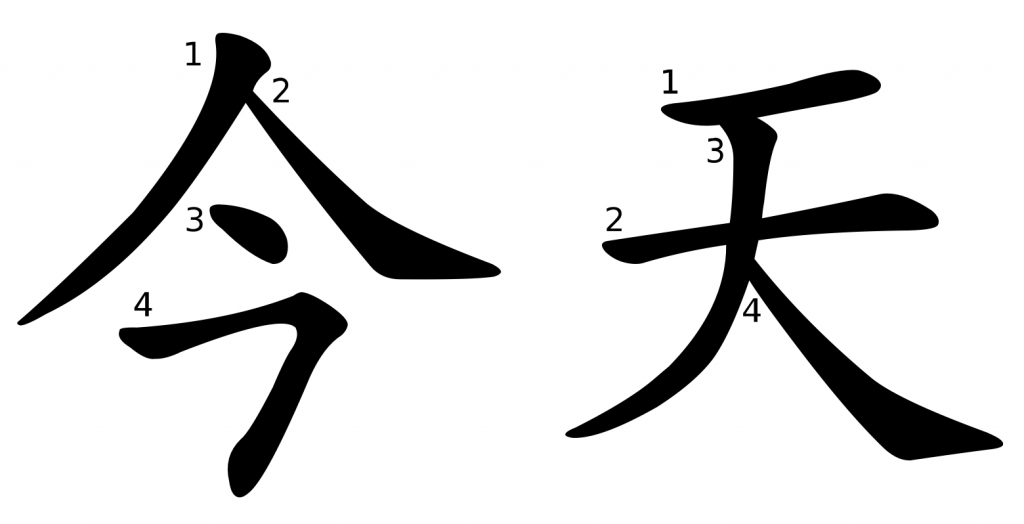

今天 n. [jīntiān] today. 今天很冷。Today is very cold.

jīn: today

radical: 人 (rén; person)

tiān: day

radical: 一 (yī; one)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

很冷 adj. [hěnlěng] cold, very cold. 今天很冷。Today is very cold.

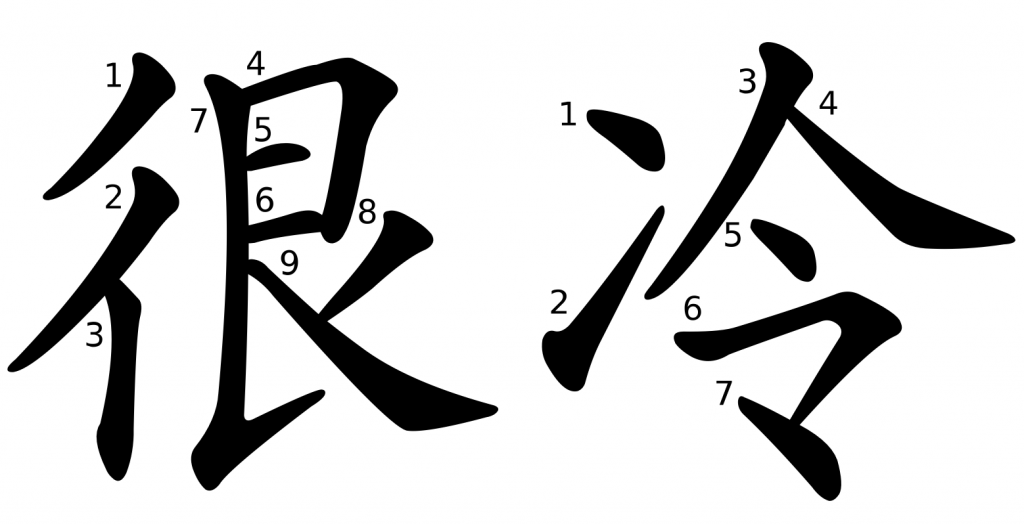

hěn: very

radical: 彳 (chì; taking small, slow steps, walking and stopping intermittently)

lěng: cold

radical: 冫(bīng; ice)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

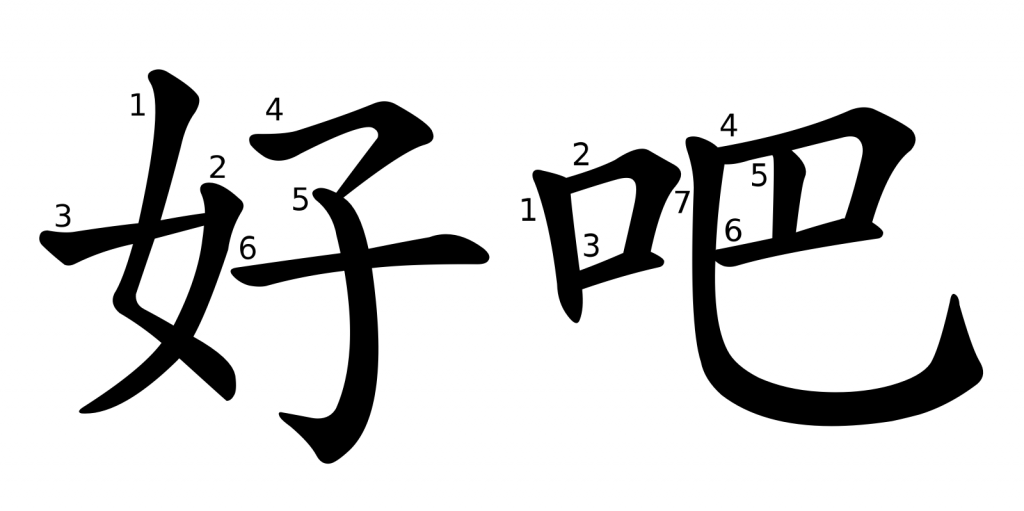

好人 NP. [hǎorén] good person. 他是好人。He is a good person.

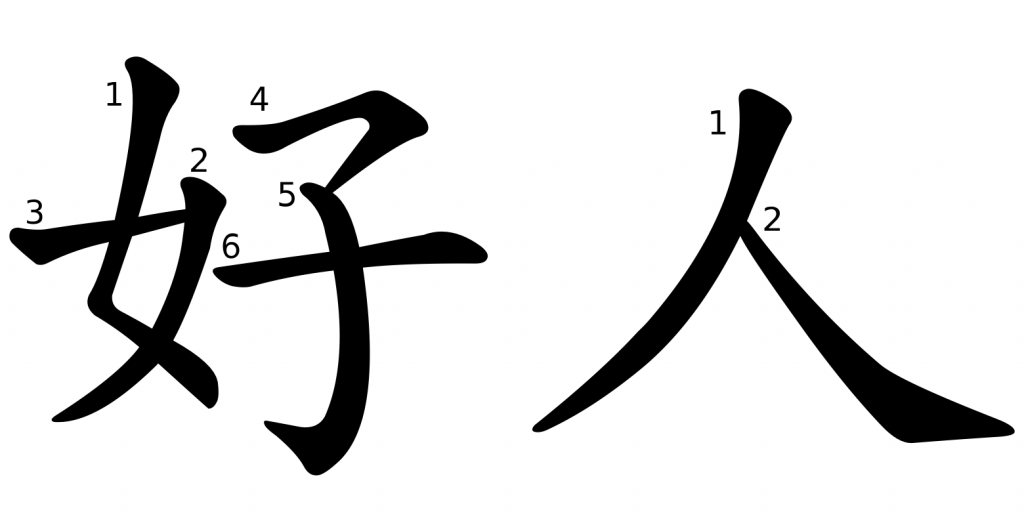

hǎo: good; nice; kind

radical: 女 (nǚ; female)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script, the left side of “好” is “女,” which can represent a woman or a mother, and the right side is “子,” which can represent a child or a male. One interpretation is that in matrilineal societies, women were highly respected, partly due to their ability to bear and raise children. The meaning of “好” as “good” or “beautiful” likely stems from this association with women’s role in reproduction and child-rearing. In ancient times, the act of women giving birth and raising children was regarded as a virtue, which led to the extension of the meaning of “good” or “beautiful.”

rén: person; people; human

radical: 人 (rén; person)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

你好嗎/你好吗 [nǐhǎo ma] How are you?

nǐ: you

radical: 亻(rén; person)

hǎo: good; nice; kind

radical: 女 (nǚ; female)

ma: The Chinese character “嗎” (simplified: 吗, pinyin: ma) is a question particle used at the end of a sentence to indicate a yes-or-no question. It doesn’t carry a specific meaning on its own but changes a statement into a question. For example, 你好嗎/吗?(Nǐ hǎo ma?) – How are you?

radical: 口 (kǒu; mouth)

Simplified character:

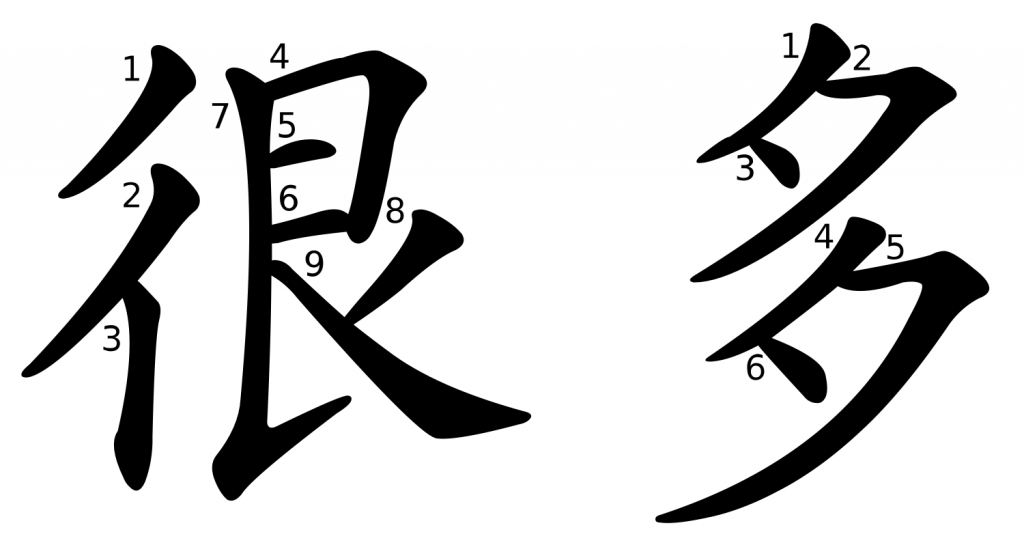

很多 adj. [hěnduō] a lot of, a lot. 很多。a lot.

hěn: very

radical: 彳 (chì; taking small, slow steps, walking and stopping intermittently)

duō: many; much; a lot

radical: 夕 (xī; evening)

Chinese Studies Classroom: “多” is formed with “夕” (evening), indicating something that accumulates or grows in quantity.

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

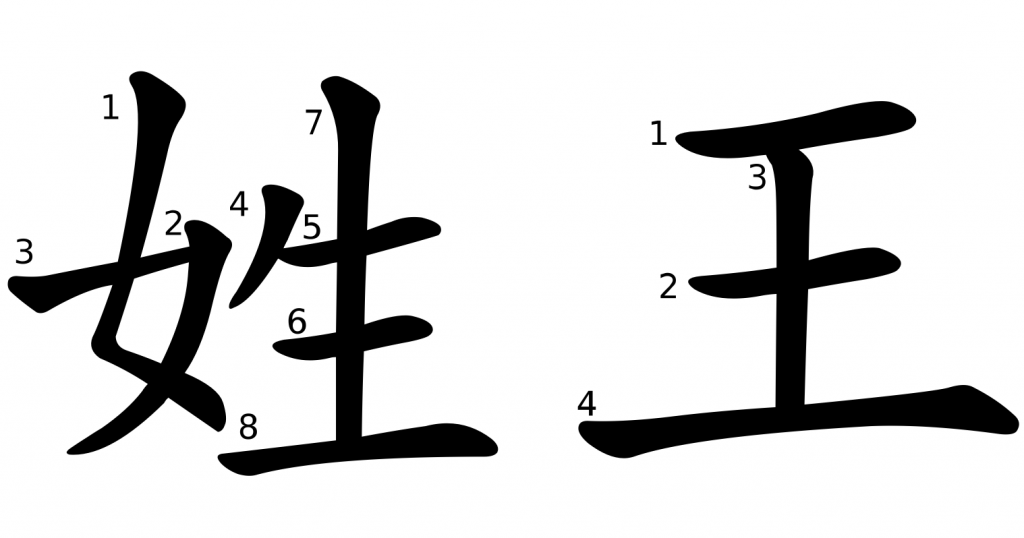

姓王 VP. [xìng wáng] the last name is Wang. 我姓王。My last name is Wang.

xìng: last name; surname

radical: 女 (nǚ; female)

wáng: A typical Chinese surname; king

radical: 王 (wáng/yù; jade)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

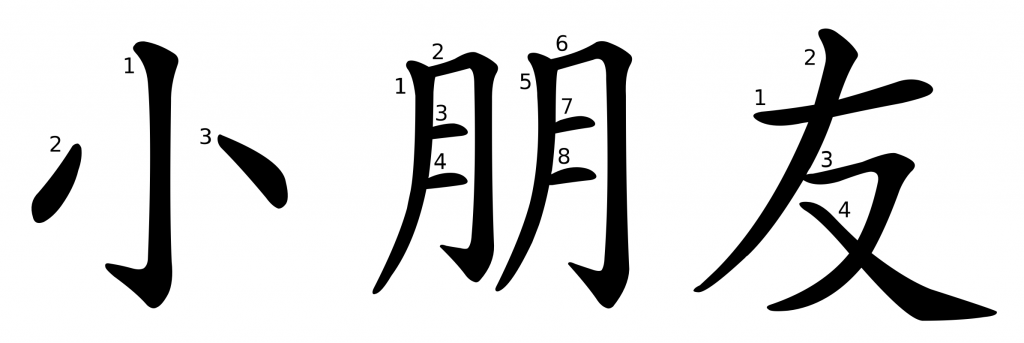

小朋友 NP. [xiǎo péngyou] children, little friend, little kid. 小朋友,你叫什麼?/ 小朋友,你叫什么?Little one, what is your name?

xiǎo: small

radical: 小 (xiǎo; small)

péng: friend

radical: 月(yuè; moon, flesh or a string of coins)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The character “朋” (péng) originally depicted two shells side by side and historically represented a “pair” or “set,” as shells were used as currency in ancient China. This pairing concept extended to mean “friends” or “companions,” as it implies two individuals linked closely, much like a pair.

yǒu, friend; friendly

radical: 又 (yòu; hand)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

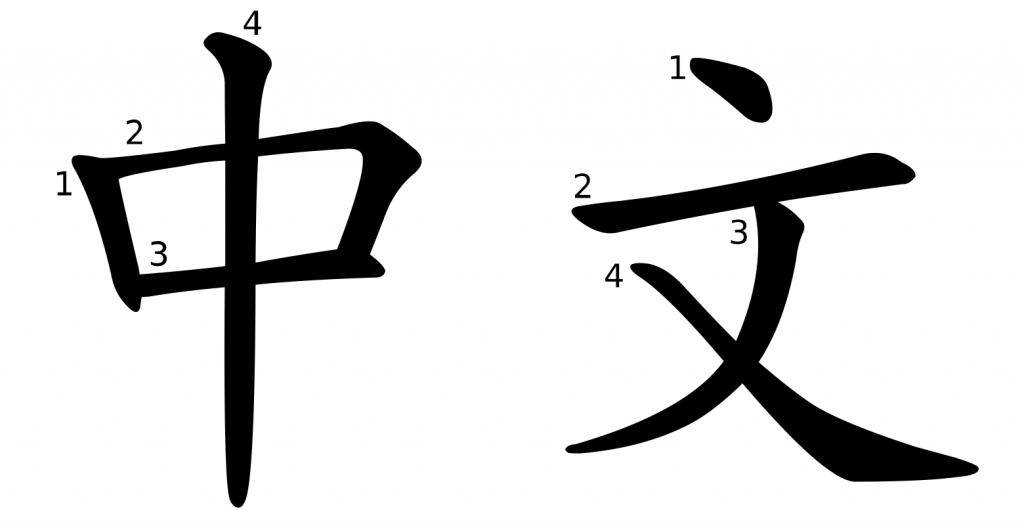

中文 n. [zhōngwén] the Chinese language. 中文很美。Chinese is beautiful.

zhōng: middle

radical: 丨 (gǔn; the way it goes up and down)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script, the character “中” resembles an upright flag, with two flag tassels at the top and bottom fluttering in the wind. The “口” in the middle of the two tassels represents the meaning of “center.”

wén: character; script; writing

radical: 文 (wén; decorative pattern)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script, the character “文” resembles the figure of a standing person. Its original meaning referred to “tattoos” and was later extended to signify patterns and textures. Over time, it further evolved to encompass meanings such as writing, adornment, civil and military matters, astronomy, and more.

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

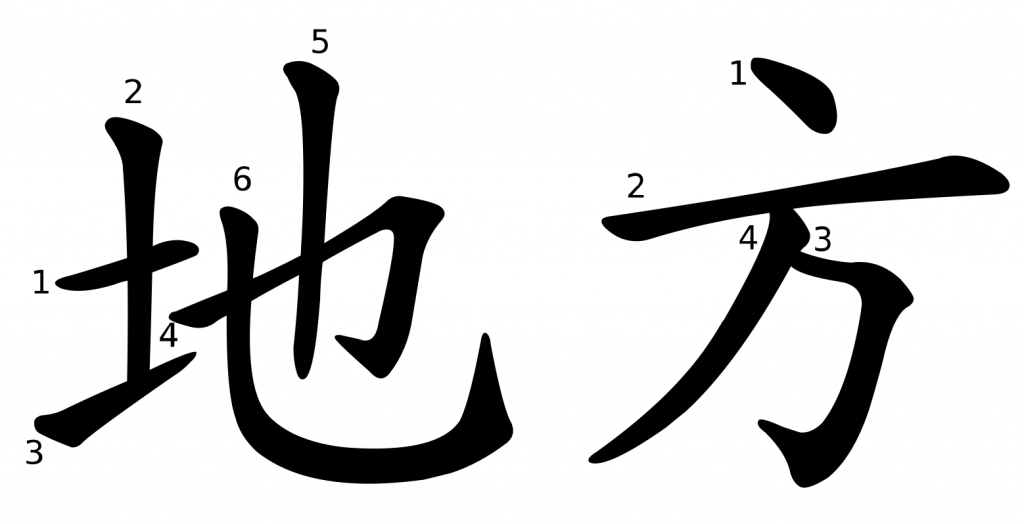

地方 n. [dìfang] place. 你是什麼地方人/你是什么地方人?Where are you from?

dì: land, ground

radical: 土 (tǔ; soil; earth)

fāng: square

radical: 方 (fāng; square)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

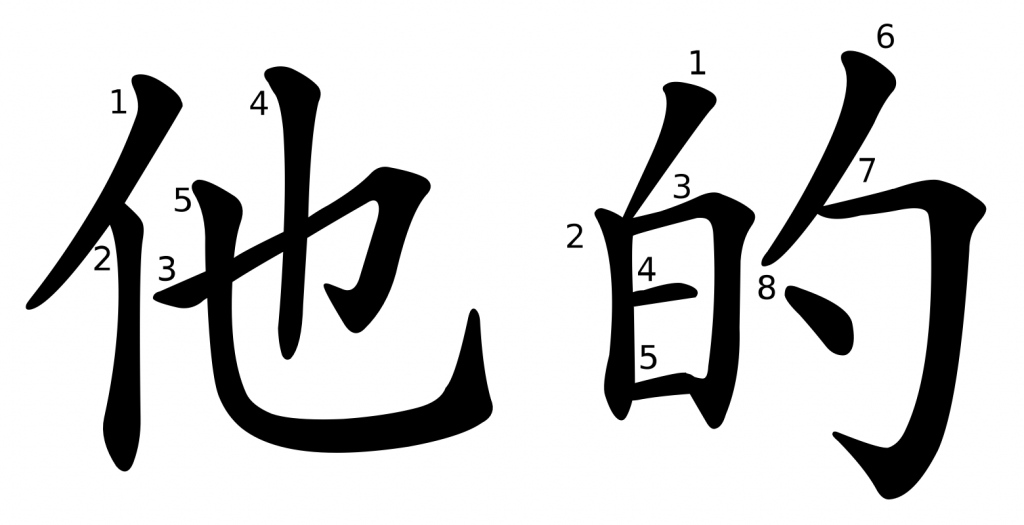

他的 pron. [tāde] his. 他的中文很好。His Chinese is very good.

tā: he; him

radical: 亻 (rén; person)

de: of

radical: 白 (bái; a sharp, bright look)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

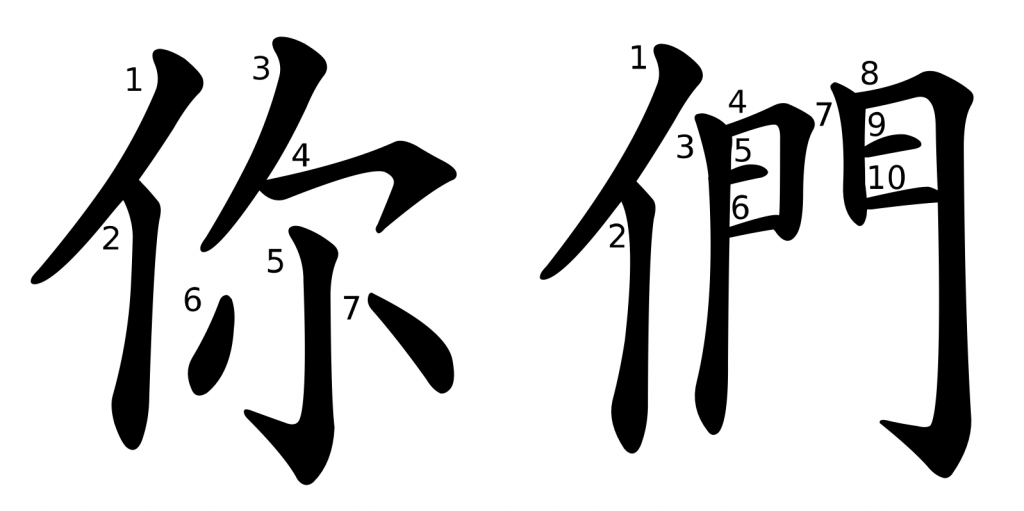

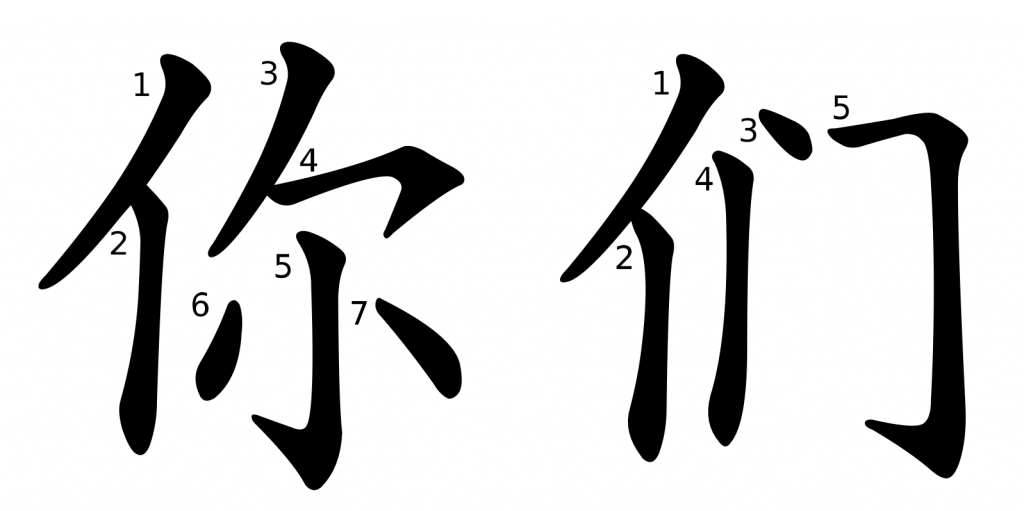

你們/你们 pron. [nǐmen] you (plural). 你們好嗎/你们好吗?How are you all?

nǐ: you

radical: 亻 (rén; person)

men: plural marker for pronouns and a few animate nouns

radical: 亻 (rén; person)

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

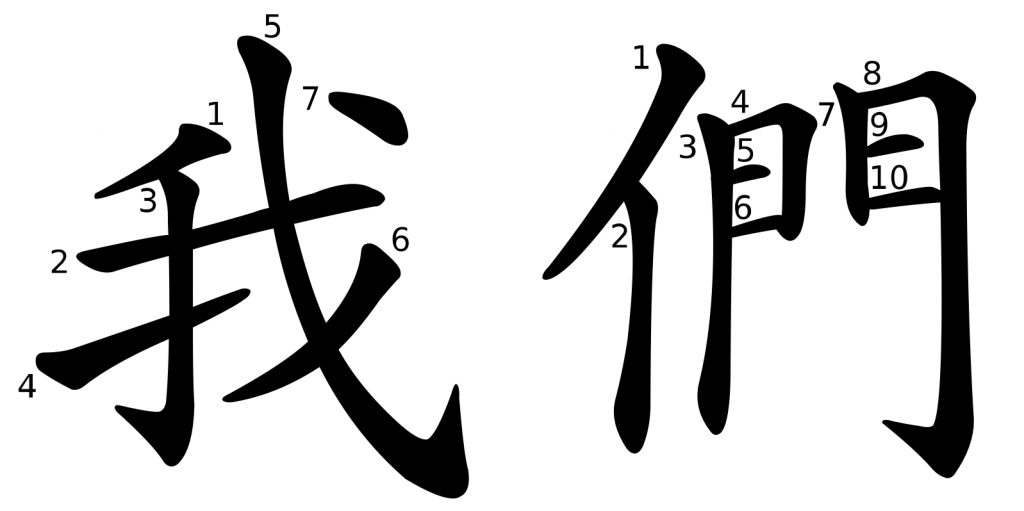

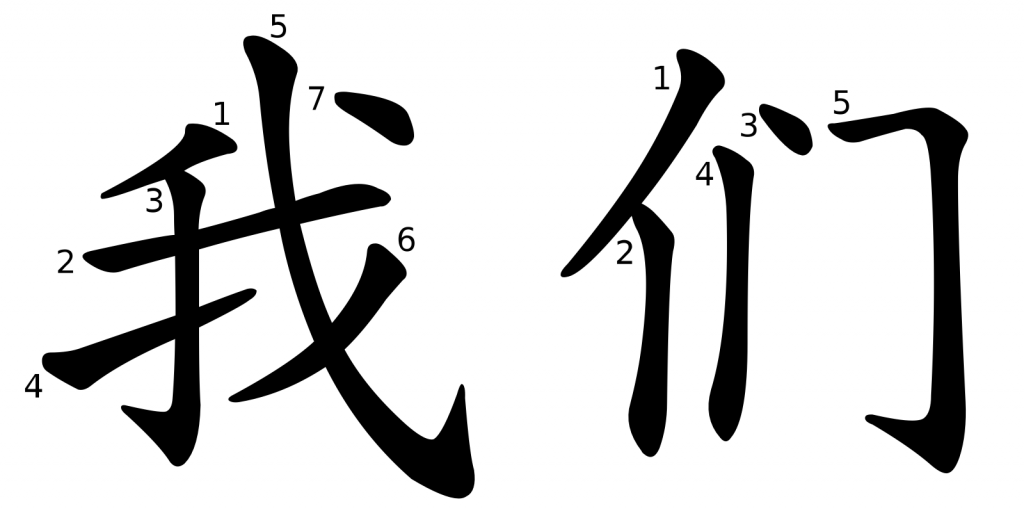

我們/我们 pron. [wǒmen] we, us. 我們很好/我们很好。We are doing well.

wǒ: I; me

radical: 戈 (gē; an ancient weapon called the dagger-axe)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The original meaning of the character “我” in oracle bone script referred to a deadly weapon used in slave society for executions and butchering livestock. From this original meaning, it extended to signify “wielding a large axe while shouting and demonstrating power.” However, by the Warring States period, the weapon represented by the original meaning of “我” had been replaced by more advanced weapons. As a result, the character “我” came to be widely used as a first-person pronoun.

men: plural marker for pronouns and a few animate nouns

radical: 亻 (rén; person)

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

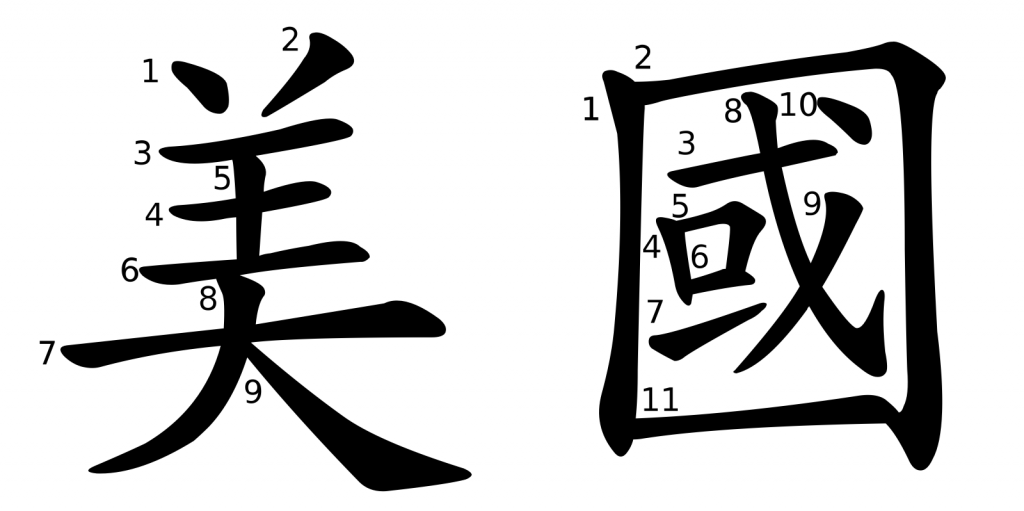

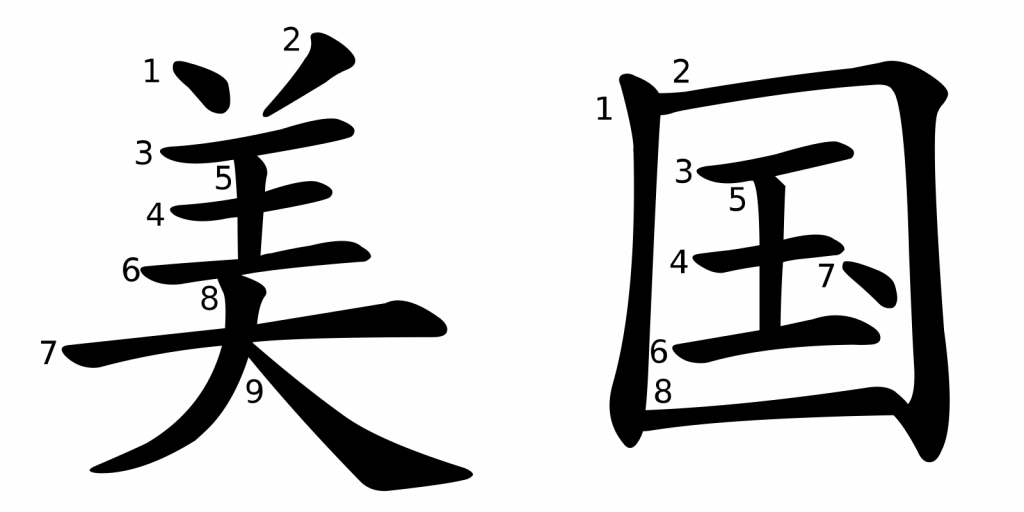

美國/美国 n. [Měiguó] America, the United States. 你是美國人嗎/你是美国人吗?Are you American?

měi: beautiful

radical: 羊 (yáng; sheep)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script, the character “美” resembles a person standing while wearing a headdress. Its original meaning refers to beauty or being attractive.

guó: country

radical: 囗 (wéi; surround)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The original form of the character “國” (guó) was “或” (huò). In Shang dynasty oracle bone script, the character “國”(guó) is composed of the symbol for a weapon, “戈” (gē), and the symbol for a boundary, “囗” (wéi). Together, they convey the idea that a country is a land defended by weapons.

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

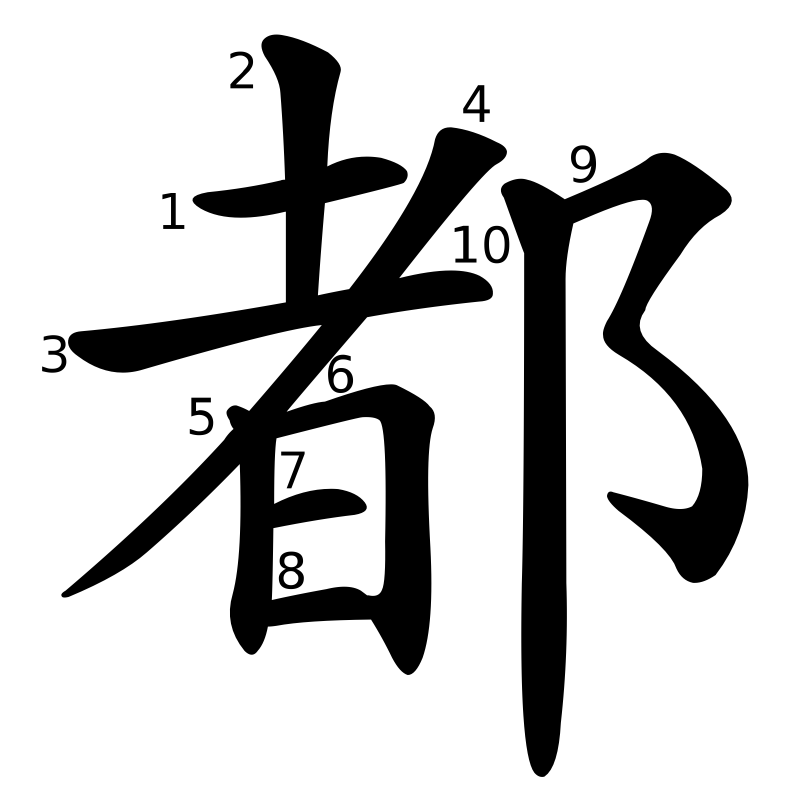

都 adv. [dōu] all. 我們都很好/我们都很好。We are all doing well.

dōu: all (adv.)

dū: capital (n.)

radical: 阝(fù; A small hill or a town)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The radical “阝” can appear on either the left or the right side of a Chinese character. When it is on the left, it is derived from the character “阜” (fù). The original meaning of “阜” is a hill, so when “阝” appears on the left side of a character, the character’s meaning is often related to mountains or terrain, such as “险” (xiǎn, dangerous), “阴” (yīn, shade), and “阳” (yáng, sun).

Chinese Studies Classroom: The radical “阝” can appear on either the left or the right side of a Chinese character. When it is on the right side, it is derived from the character “邑” (yì), which is associated with cities. Therefore, when this radical appears on the right side, the character’s meaning is often related to towns or place names, such as “都” (dū, capital), “郊” (jiāo, suburb), “邦” (bāng, state).

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

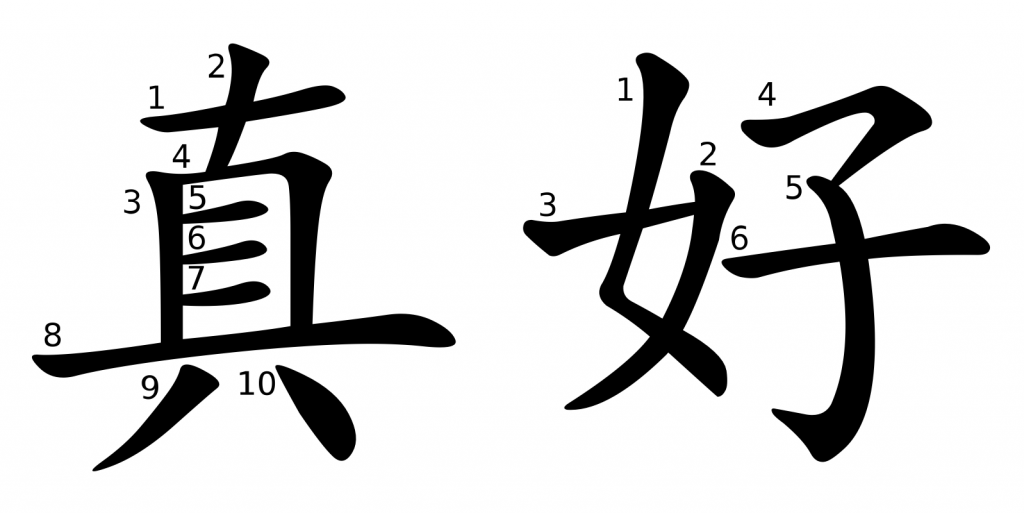

真好 VP. [zhēnhǎo] really good. 真好!That’s great!

zhēn: truth, really

radical: 十 (shí)

Chinese Studies Classroom: One interpretation is that in the bronze script, the character “真” consists of “卜” (divination) on top and “鼎” (cauldron) on the bottom. The “鼎” represents a cooking vessel, symbolizing fire. Fire was used to heat tortoise shells for divination to determine truth or falsehood.

hǎo: good; nice; kind

radical: 女 (nǚ; female)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

太好了 VP. [tàihǎole] great. 太好了!Great!

tài: too; extremely

radical: 大 (dà; big)

hǎo: good; nice; kind

radical: 女 (nǚ; female)

le: 1. Used after a verb or adjective to indicate that an action or change has been completed. 2. Used at the end of a sentence or at a pause within a sentence to indicate a change or the emergence of a new situation.

radical: 乛

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

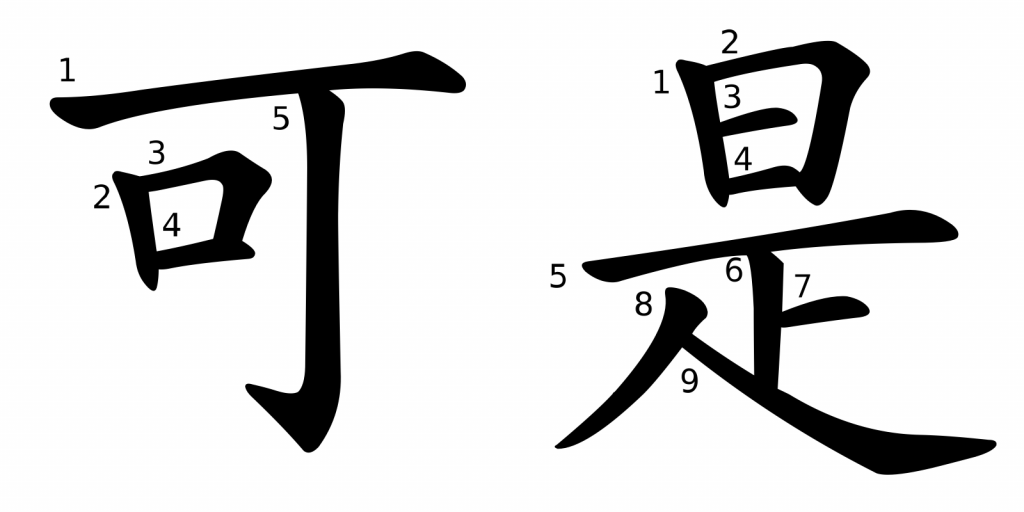

可是 conj. [kěshì] but, however. 他是好人,可是我不喜歡他。/ 他是好人,可是我不喜欢他。He is a good person, but I don’t like him.

kě: “可” combined with “是” can indicate a contrast, while “可” combined with “以” can indicate permission.

radical: 口 (kǒu, mouth)

shì: be; is; are

radical: 日 (rì, sun)

Chinese Studies Classroom: One explanation is that in the Bronze Script, the character “是” consists of a sundial on top and the character “正” (upright) below, with the basic meaning of upright and not skewed. It later extended to mean correctness and further evolved into a response word, expressing agreement or approval. After the Han dynasty, “是” was used as a copula to indicate judgment.

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

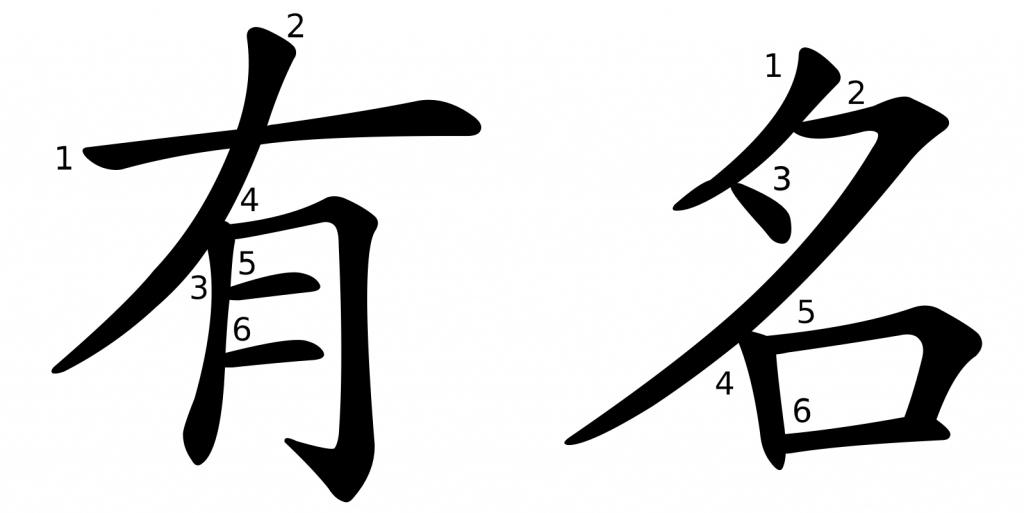

有名 adj. [yǒumíng] famous. 他很有名。He is very famous.

yǒu: to have

radical: 月 (yuè, flesh)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In Western Zhou Bronze Script, the upper right part of the character “有” represents a hand, while the lower left part depicts a piece of meat, resembling the cross-section of meat. It signifies having meat in hand, meaning “having“ food.

míng: to have

radical: 夕(xī, night) and 口 (kǒu, mouth)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In Oracle Bone Script, the character “名” is composed of “口” (mouth) and “夕” (night). In ancient times, when people traveled at night and couldn’t see each other, they would call out their own names. Therefore, the meaning of “名” is name.

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

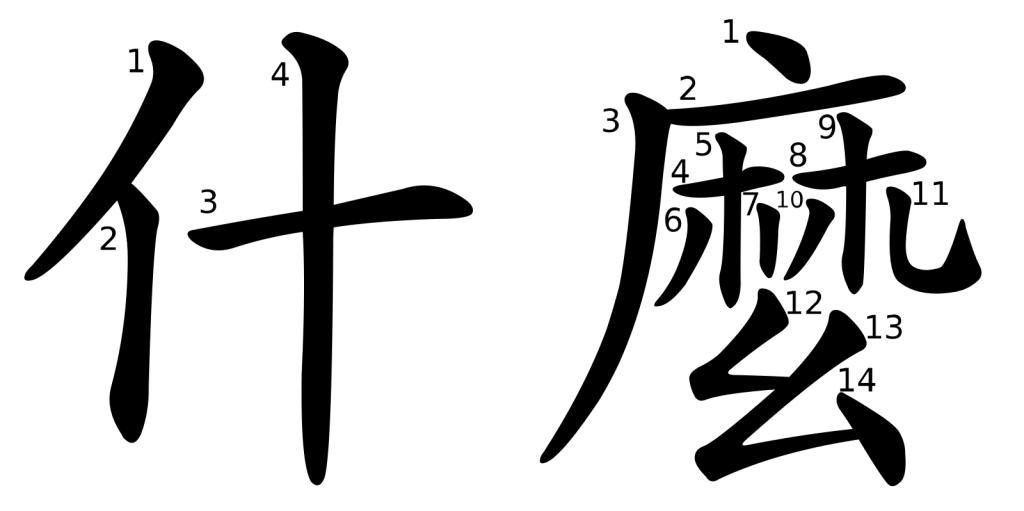

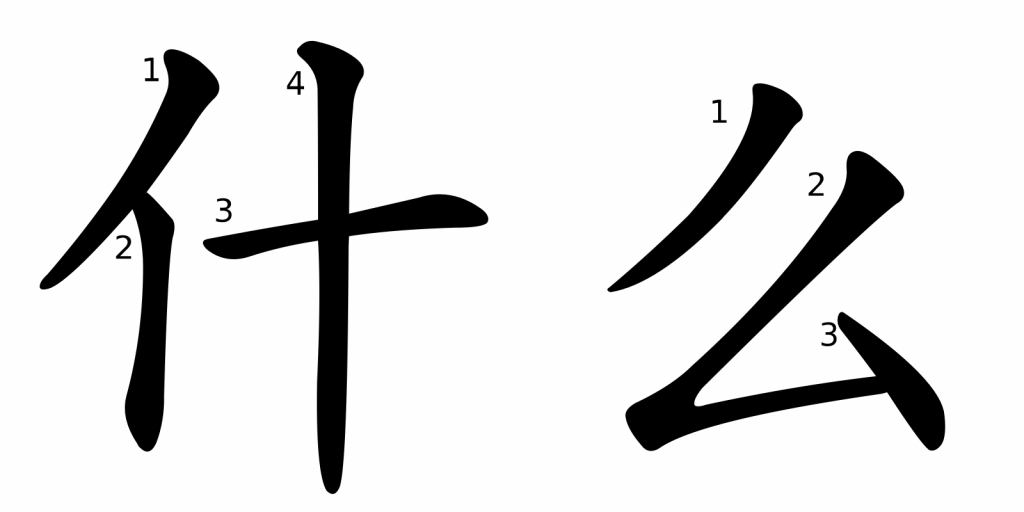

什麼/什么 pron.&det. [shénmo] what. 你叫什麼/你叫什么?What’s your name?

shén: Interrogative pronoun, when used with “麼/么,” can express the meaning of “what.”

radical: 亻(rén, person)

mo: Suffix, when combined with “什” to form “什麼,” can express the meaning of “what.” The original meaning refers to small or tiny. Later, it evolved into a modal particle.

radical: 广 (guǎng; the house on the cliff)

Characters with “广” as a semantic component are mostly related to buildings or places, such as 庭 (tíng; courtyard), 店 (diàn; shop) and 庫/库 (kù; storehouse)

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

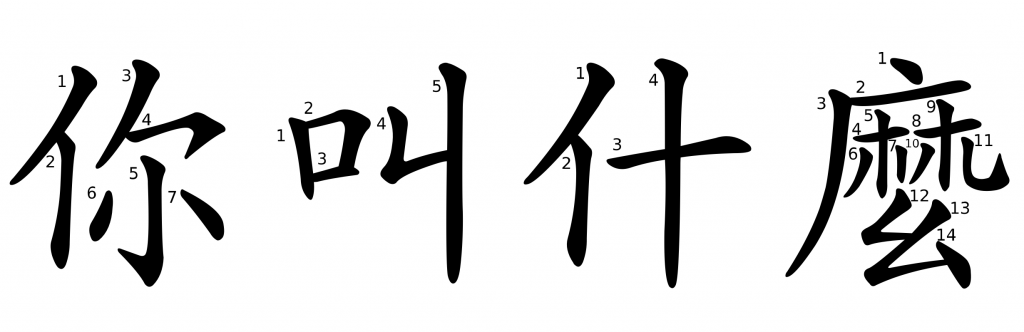

你叫什麼/你叫什么 [Nǐ jiào shénme] What’s your name?

jiào: v. call; name; cry

radical: 口 (kǒu, mouth)

Chinese characters with the “口” radical are often related to the mouth, such as: 問/问 (to ask), 叫 (to call), 唱 (to sing), 喝 (to drink) and 吃 (to eat)

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

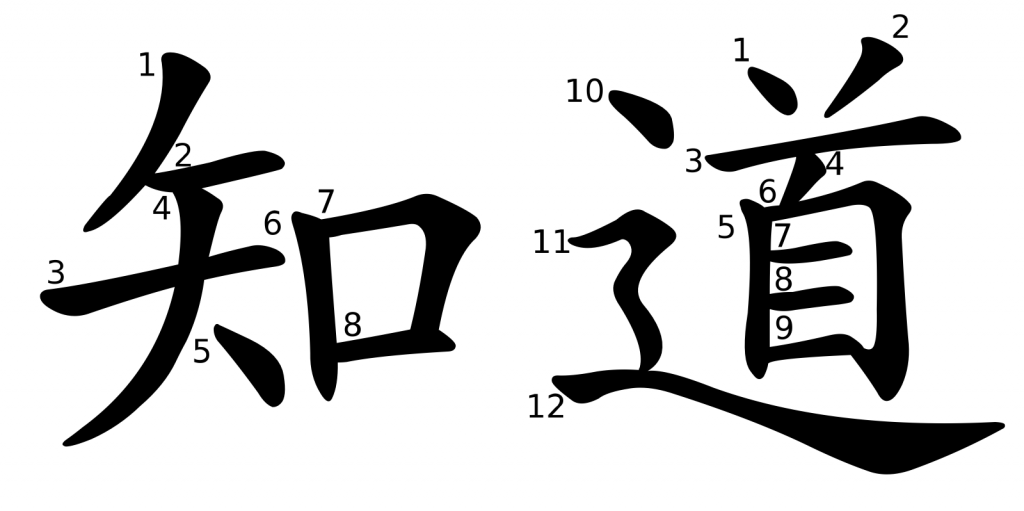

知道 v. [zhī.dào] know. 我知道。I know.

zhī: know

radical: 口(kǒu, mouth)

dào: way; road; method

radical: 辶 (chuò,walking)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The “辶” radical, also known as “chuò” or “walking” radical, is associated with movement, walking, or travel. It is a simplified form of the character “辵,” which depicts a combination of “止” (a foot or stop) and a repeated “彳” (a step or walking action). When this radical appears in characters, it often conveys meanings related to movement, direction, paths, or travel. For example, 進/进 (jìn, to enter), 遠/远 (yuǎn, far), 送 (sòng, to send) or 道 (dào, path, way)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

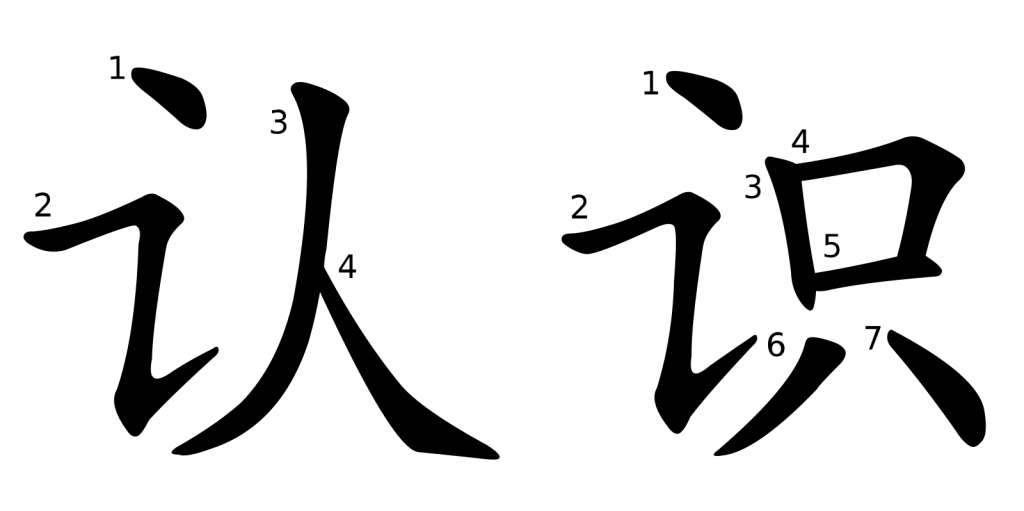

認識/认识 v. [rèn.shí] acquaint oneself with, acquaintance. 我認識他/我认识他。I know him.

rèn: recognize; know; identify

radical: 言 (yán, language)

shí: know; understand

radical: 言 (yán, language)

Simplified character:

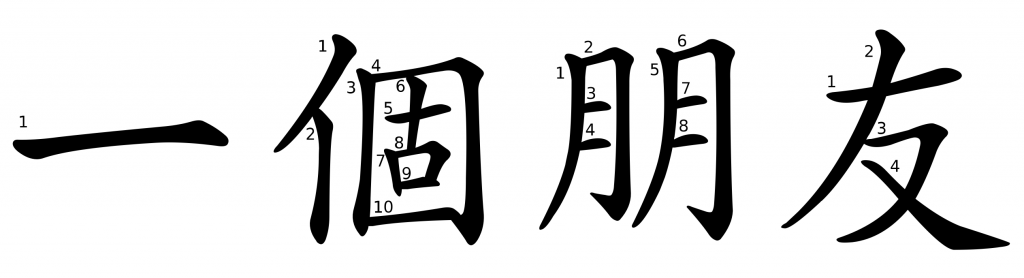

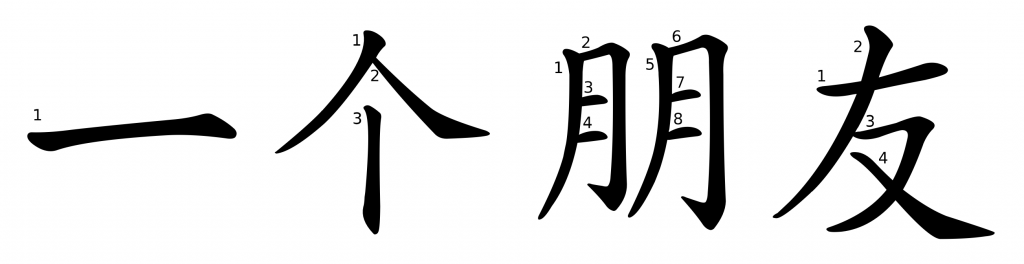

一個朋友/一个朋友 NP. [yíge péngyou] a friend. 我有一個朋友/我有一个朋友。I have a friend.

yī: one

radical: 一

gè: Used as a measure word, it also refers to size, body shape, or the dimensions of an object.

radical: 亻(rén, person)

Traditional character:

Simplified character:

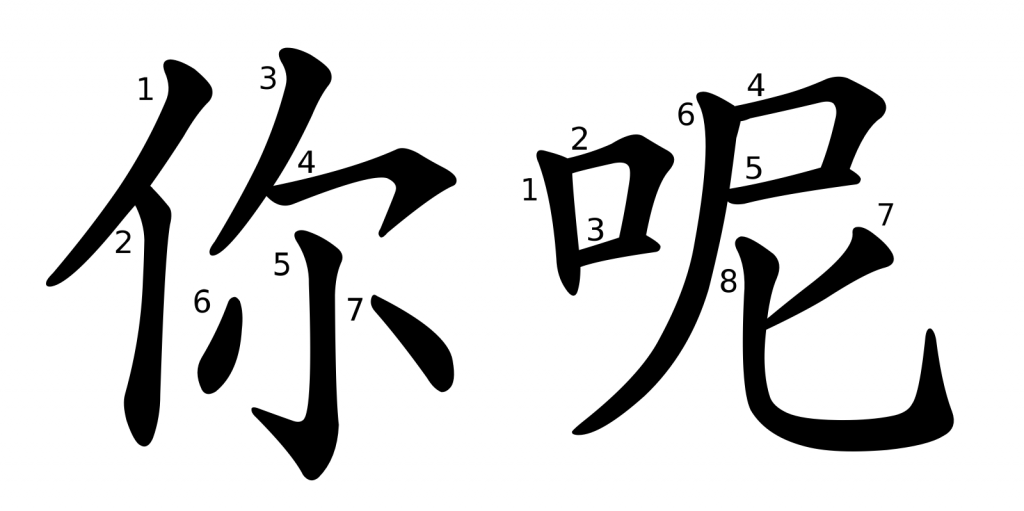

你呢 [nǐne] What about you?

ne: Used as a particle, placed at the end of a sentence. For example, 你呢? (How about you?)

radical: 口 (kǒu, mouth)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

好吧 [hǎoba] all right, OK.

ba: Used as a particle, placed at the end of a sentence to indicate agreement, speculation, command, request, or other moods. For example: 好吧 (OK).

radical: 口 (kǒu, mouth)

Both traditional and simplified characters are written as:

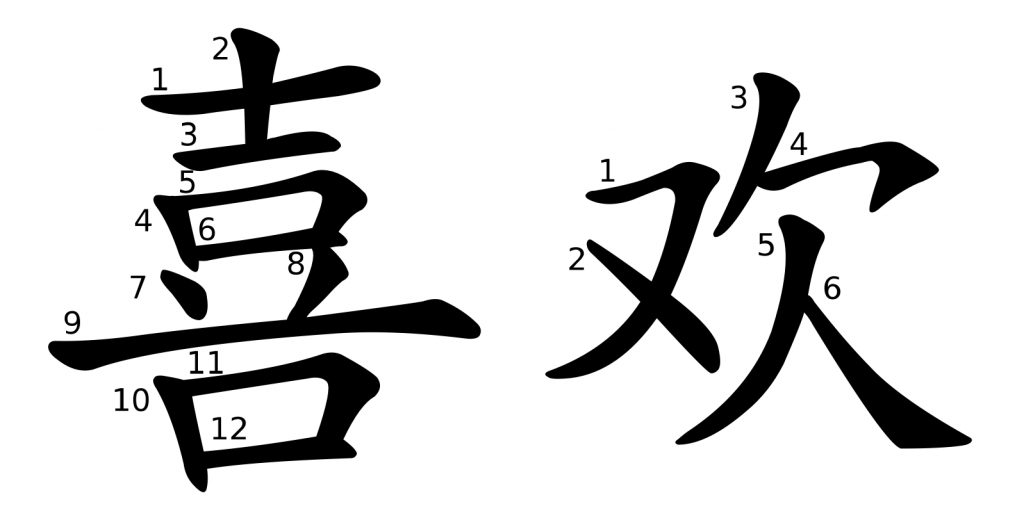

喜歡/喜欢 v. [xǐhuan] like. 我喜歡你/我喜欢你。I like you.

xǐ: happy

radical: 口 (kǒu, mouth)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script, the upper part of “喜” is “壴” (zhù), which resembles the shape of a drum. The lower part is “口,” representing a person. The combined meaning is: upon hearing the sound of drums, one would joyfully laugh with delight.

huān: joyous

radical: 欠 (qiàn, The shape of this character looks like a person opening their mouth to exhale)

Chinese Studies Classroom: The original meaning of “歡” is “happiness” or “joy.” The component on the left, “雚,” in ancient times represented sound, while the component on the right is the radical “欠.” The shape of “欠” resembles a person opening their mouth to exhale.

Simplified character:

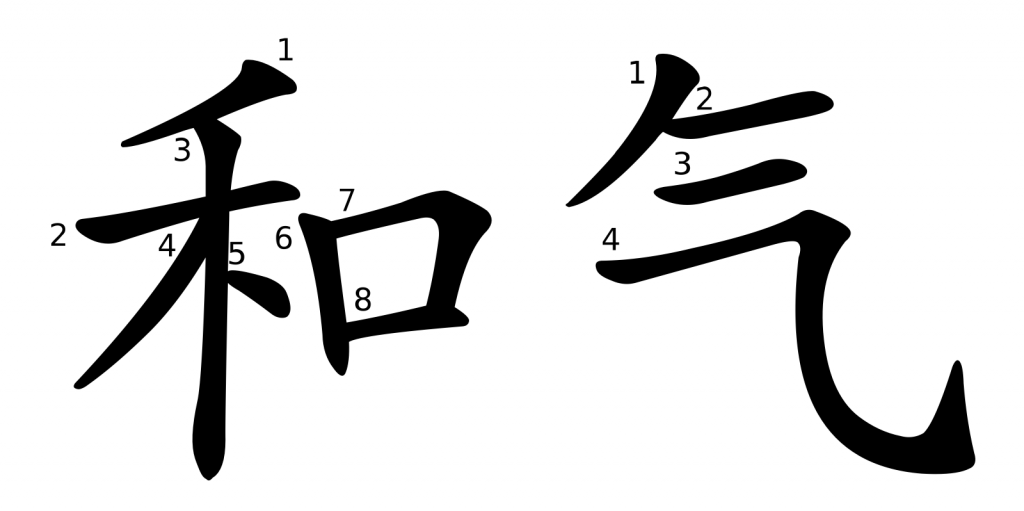

和氣/和气 adj. [héqi] gentle, kind. 她很和氣/她很和气。She is very friendly.

hé

adj. gentle, harmonious

prep. with

conj. and

radical: 禾(hé, standing grain) and 口 (kǒu, mouth)

qì: air; gas

radical: 气 (qì, air)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script, the character “氣” is written as three horizontal lines, simulating the state of clouds or air floating in the sky. It later extended to mean “air” or “gas.”

Simplified character:

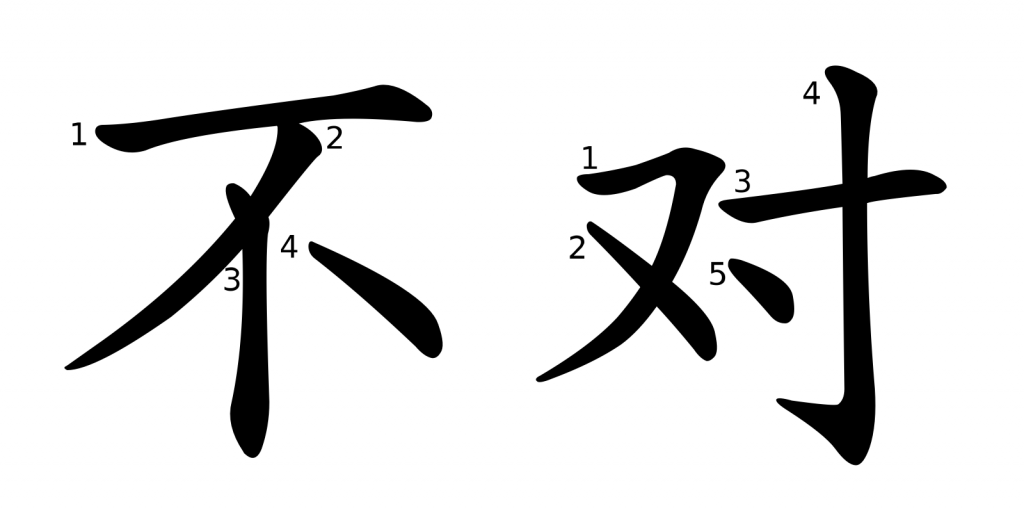

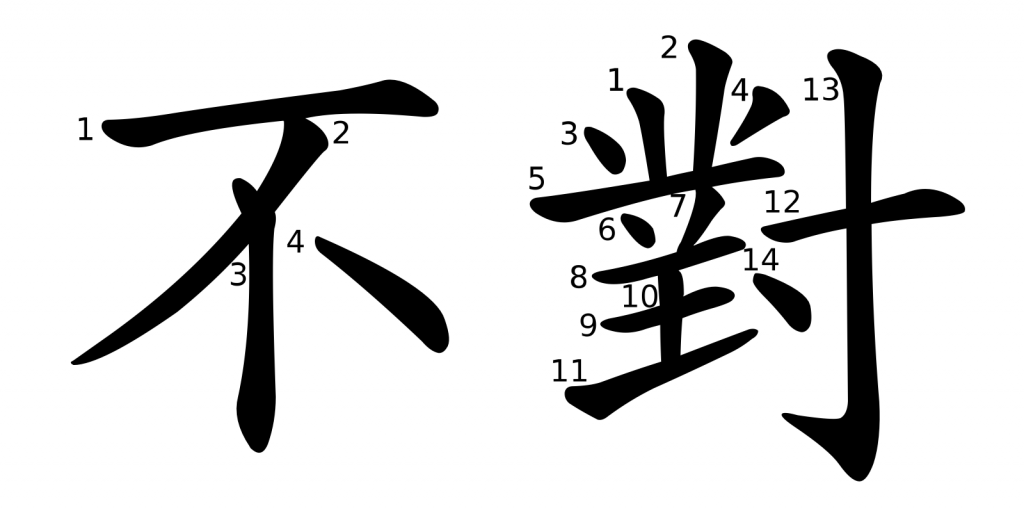

不對/不对 VP. [búduì] not right.

bù: no; not; don’t

radical: 不

duì: correct

radical: 寸 (cùn)

Chinese Studies Classroom: In oracle bone script and bronze script, the character “對” is formed to resemble holding something with hands. Its original meaning refers to responding or answering. From the interaction between the parties responding, it extended to mean opposition, and also came to represent pairs or matching. It further extended to mean verification. In modern Chinese, “对” also means correct, in contrast to incorrect.

Traditional character:

Simplified character: